A critical voice in contemporary public art, Dennis Adams interrogates the aesthetics and politics of the cityscape, the meaning and experience of public space. Through site-specific installations and urban interventions, Adams questions how the built environment and media archives structure our relationship to history, memory, and ideology. His work resists passive reception, instead inviting – and often confronting – viewers with the entangled narratives of power and representation, rooted in the belief that the city is both a site of power and a contested field of representation.

The Bus Shelters: Everyday Architecture and Urban Intervention

Among Adams’ most iconic and influential projects is his Bus Shelter series, begun in the early 1980s. These architectural interventions transform everyday urban infrastructure into provocative stages for reflection and resistance. Each shelter integrates photographic and textual content into the structure itself, creating a collision between everyday utility and historical consciousness. Adams thus reclaims spaces of passive waiting and transforms them into active sites of political confrontation.

Bus Shelter I (1983), installed at Broadway and 66th Street in New York and later exhibited at the Israel Museum, divides its photographic panel between an image from the McCarthy Army Hearings and a textual contribution by Jenny Holzer. The shelter becomes a confrontation between public propaganda and private reflection.

In Bus Shelter II (1986), the viewer encounters an image of Ethel and Julius Rosenberg – figures symbolizing Cold War paranoia – fragmented by the very architecture that houses it. Here, the shelter was sited on 14th Street in New York and acquired by the National Museum of American Art, Washington, D.C.

Dennis Adams, "Bus Shelter IV", 1987

Bus Shelter IV, created for Skulptur Projekte Münster in 1987, amplifies these tensions. Located at Domplatz, this shelter crops and magnifies a courtroom image from the Klaus Barbie trial. The structure, divided into mirror-image seating areas, includes duplicated panels showing Jacques Vergès and Barbie in court, while the inner panels isolate and enlarge an anonymous bystander from the trial. The work implicates spectatorship itself, posing ethical questions about complicity, history, and the role of the observer.

Commissioned by Kunsthalle Bielefeld for its 50th anniversary, Bus Shelter 12: Shattered Glass / The Confessions of Philip Johnson critically engages the Kunsthalle’s architect, Philip Johnson, not only as a formal innovator but as a historical figure shaped by aesthetic and political contradictions. The shattered glass wall bisects the space and introduces a confessional-style video installation, delivered in both English and German, based on a first-person text written by Adams. Viewers are caught in the act of waiting, but also reading, reflecting, and re-evaluating.

Airborne: A Quiet Politics of Mourning

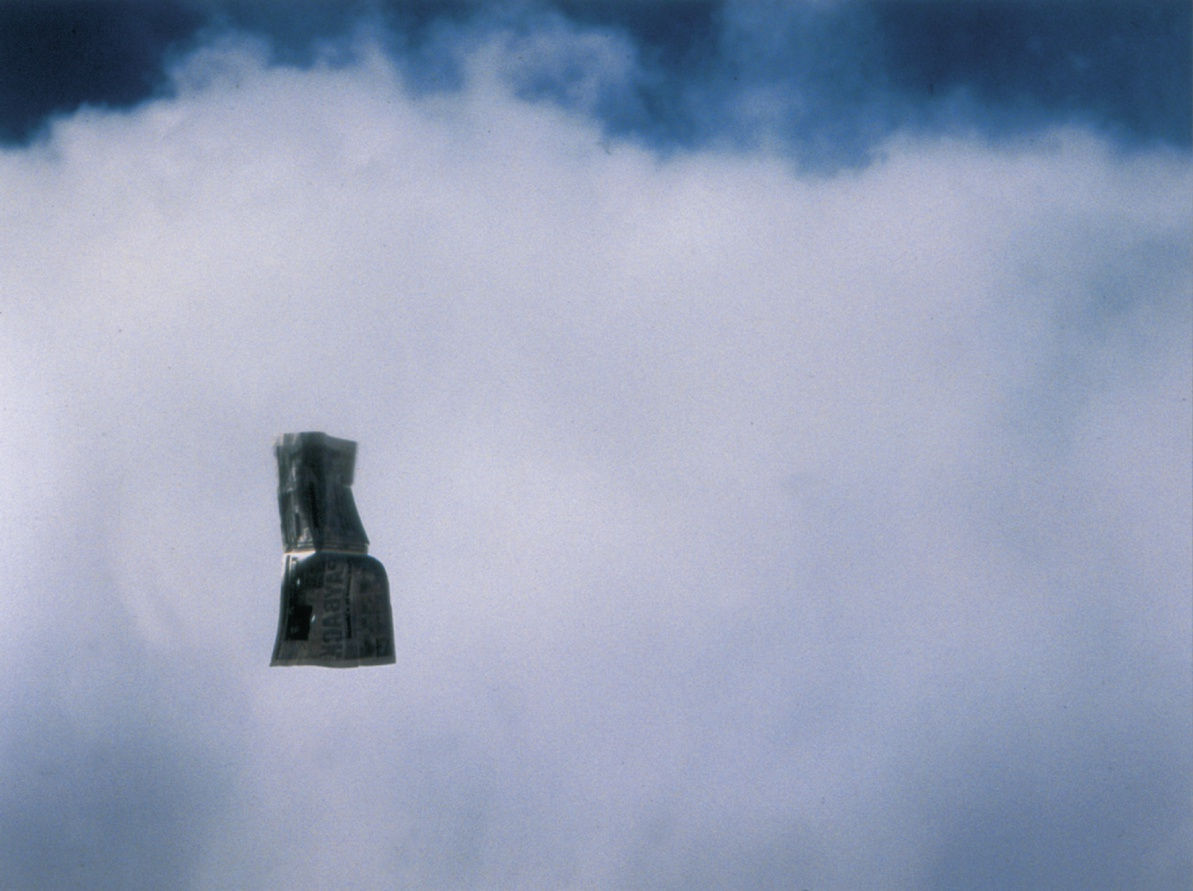

With Airborne (2002), Adam responds to the aftermath of 9/11, drawing from his own experience living near Ground Zero. The series is haunted by the visual and emotional debris of the attack. Floating fragments of paper, silence interrupted by jet sounds, altered street routines – all become part of a landscape of disorientation and mourning. Adams refrains from overt symbolism, choosing instead to dwell in the “peripheral incident,” the quiet aftermath that resists easy narration. The political potency of Airborne lies in its refusal to monumentalize or explain trauma, opting instead to expose the fragility and precarity of urban life in crisis. By pointing to the sky, which has become a harbinger of catastrophe, Adams reflects on the ways in which 9/11 not only shattered physical space but also realigned the psychic and political space of the public sphere.

Dennis Adams, "Airborne: Payback", 2002

Outtake: Fragmented Narratives

In Outtake (1998), Adams extracts a 17.33-second shot from Ulrike Meinhof’s television film Bambule and presents it as 416 individual film stills in order. These stills are handed out, documented with an arm-mounted video camera, to passersby on Berlin’s Kurfürstendamm.

The result is a hybrid between performance, video, and documentary – a live transmission of the image as artifact and ephemera. The narrative itself portrays a humiliating sequence of an adolescent girl chased by nuns intent on cutting her hair – resonates as a symbol of control, institutional violence, and the politics of visibility.

The Cityscape as Archive: Adams’ Ongoing Relevance

Adam’s choice of working through interventions into street architecture would reintroduce events that people chose to forget. He always treated public space not as neutral territory, but as a contested terrain where the ideology was presented to a captive audience.

His interventions remind us that architecture, photography, and media are not passive reflections of reality; they are tools that can be manipulated to expose the mechanisms of power. Adams doesn’t offer easy answers. He stages confrontations, asking us to re-read the familiar images and spaces we inhabit.

Adams’ commitment to political art is not didactic but dialogic. His projects activate the city as a site of inquiry, provoking questions about who controls space and how history is written into it. He insists that the politics of public space are inseparable from broader questions of power and visibility. His interventions provoke a reactivation of public perception, an invitation to think critically in and with the city.

In Adams’ work, the city becomes a living archive whose gaps, contradictions, and silences are brought to the surface, inscribed into the structures we move through every day. His work asks us to look more carefully at the spaces we inhabit.

Learn more about the Kent Fine Art gallery and make sure to explore our list of artists.